Quand | When

12.04.2017 | 20h00

Où | Where

la lumière collective

7080, rue Alexandra, Montréal [QC]

Média | Media

16mm | HD

En présence du directeur Benjamin Cook

Billets | Tickets

7$ à la porte

Its film workshop enabled artists to control every stage of the filmmaking process; a creative freedom that was often extended, through the creation of expanded cinema works, to the moment of projection.

Initialement fondée au mois d’octobre 1966 en tant qu’association non-commerciale de distribution de films expérimentaux, le mandat de la London Film-Makers’ Co-operative s’est rapidement élargi afin de donner accès à une infrastructure pour la production cinématographique et développer ainsi un espace pour mener des investigations radicales sur le film comme matériel.

LUX | LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ CO-OPERATIVE

Initialement fondée au mois d’octobre 1966 en tant qu’association non-commerciale de distribution de films expérimentaux, le mandat de la London Film-Makers’ Co-operative s’est rapidement élargi afin de donner accès à une infrastructure pour la production cinématographique et développer ainsi un espace pour mener des investigations radicales sur le film comme matériel. Ces ateliers d’expérimentation ont permis aux artistes d’être en contrôle à chacune des étapes de la production cinématographique; une liberté de création qui se constatait par, entre autre, la création d’œuvres de cinéma élargi, ainsi qu’au moment de la projection.

Gérée collectivement et majoritairement de manière bénévole, la LFMC opère sans financement à ses débuts. Toutefois, elle a réussi à maintenir ses activités de distribution, son espace de présentation et à réaliser ses ateliers de création dans chacun de ses bâtiments industriels délabrés où elle se situait. De cet environnement à la fois précaire et stimulant est né un corpus remarquable de films et d’oeuvres théoriques avant-gardistes faisant échos à la diversité artistique actuelle dans le domaine des arts médiatiques et du cinéma.

Afin de célébrer le lancement du livre récemment publié intitulé Shoot Shoot Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative 1966-76 (édité par Mark Webber et publié par LUX), nous vous présentons une soirée de films classiques issus de cette époque pionnière de production cinématographique artistique en Grande-Bretagne. Le programme sera présenté par Benjamin Cook, directeur de LUX.

Les films du programme sont réalisés par Lis Rhodes, Simon Hartog, Peter Gidal, John Smith, Mike Leggett, Marilyn Halford et un film/performance dit de cinéma élargi de Malcom Le Grice sera également présenté.

Initially founded in October 1966 as a non-commercial distributor of experimental films, the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was soon reconfigured into a unique organisation that provided access to production facilities and developed a context for radical investigations of film as material. Its film workshop enabled artists to control every stage of the filmmaking process; a creative freedom that was often extended, through the creation of expanded cinema works, to the moment of projection.

Collectively run on a largely voluntary basis, the LFMC operated without funding throughout its early years. Nonetheless, it maintained a distribution office, cinema space and film workshop in each of the run-down, former industrial buildings in which it was based. This precarious but supportive environment stimulated a remarkable body of films and theoretical work that anticipated today’s diverse culture of artists’ moving image.

To celebrate the Canadian launch of the new book, Shoot Shoot Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative 1966-76 (edited by Mark Webber and published by LUX) we present an evening of classic films from this pioneering period of artists’ filmmaking in the UK introduced by Benjamin Cook, Director of LUX.

Including films by Lis Rhodes, Simon Hartog, Peter Gidal, John Smith, Mike Leggett, Marilyn Halford and a Malcolm Le Grice expanded film performance.

“SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT”

The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative 1966-76

[Book Launch + Screening]

19h00 | 60 min

Lis Rhodes | UK |1971 – 1972 | 16mm to digital | colour | 5 min

Était peut-être posée la question du son – l’incertitude de toute synchronisation entre ce qui a été vu et ce qui a été dit est au point de départ d’une enquête sur la relation du son à l’image. Dresden Dynamo est un film que j’ai fait en 1972 sans caméra – dans lequel l’image est exactement la piste sonore reproduite – le son piste l’image. Un film témoin. – [Lis Rhodes, traduction : PK – collectif jeune cinema]

It was perhaps the question of sound – the uncertainty of any synchronicity between what was seen and what was said that began an investigation into the relationship of sound to image. Dresden Dynamo is a film that I made without a camera – in which the image is the sound track – the sound track the image. A film document. – [Lis Rhodes]

Peter Gidal | UK | 1968 | 16mm to digital | 10 min

“Un hors lente de zoom et de défocalisation”. Une éventration clos et progressive de la progression de durée. – [Birgit Hein, Film Im métro 1971, traduction : re:voir]

An enclosed and progressive disembowelment of durational progression. – [Birgit Hein, Film Im Underground, 1971]

Marilyn Halford | UK | 1975 | 16mm to digital | 6 min

Footsteps est une sorte de jeu réincarné : le jeu entre la caméra et l’acteur, l’acteur et la caméraman, et cent pieds de film. Le film joue entre positif et négatif pour changer son propre équilibre : le noir pour la perspective, puis qui fait ombre à l’écran, et pour créer un paradoxe à propos du jeu d’acteur et de l’acte de regarder l’écran. La musique crée une atmosphère puis modifie l’espace, renvoie au positif puis silence la planéité du négatif. – [Marilyn Halford]

Footsteps is in the manner of a game re-enacted: the game in making was between the camera and actor, the actor and cameraman, and one hundred feet of film. The film became expanded into positive and negative to change balances within it: black for perspective, then black to shadow the screen and make paradoxes with the idea of acting, and the act of seeing the screen. The music sets a mood then turns a space, remembers the positive then silences the flatness of the negative. – [Marilyn Halford]

Mike Leggett | UK | 1971 | 16mm to digital | 15 min

”L’un des morceaux les plus simples est le Shepherd’s Bush de Mike Leggett. Une section de film représentant un mouvement d’avancée fut imprimé à chaque degré disponible dans la gamme des gris de l’imprimeur. Le film se structure sur la section totalement noire du début et la section sur-exposée de la fin. Un procédé purement mécanique engendre une réponse complexe alors que celui qui regarde essaie de situer l’apparition de l’image à travers le noir, se déplace continuellement, analyse encore la séquence-image, puisqu’elle se transforme de manière prévisible à la conception et imprévisible à sa représentation, et alors, perd la séquence dans une lumière accablante. Le relativisme potentiel impliqué dans le refus de chacune des séquences comme point de référence évaluateur est résumé par la conception générale du film, qui fond la structure et le procédé.

Les séquences ne sont pas appréhendées comme séparées ou opposées l’une à l’autre, mais plutôt comme le résultat nécessaire d’un processus de transformation”. – [John Du Cane, Catalogue of British Avant Garde Art 1971, traduction : CINÉDOC]

Shepherd’s Bush was a revelation. It was both true film notion and demonstrated an ingenious association with the film process. It is the procedure and conclusion of a piece of film logic using a brilliantly simple device: the manipulation of the light source in the Film Co-op printer such that a series of transformations are effected on a loop of film material. From the start, Mike Leggett adopts a relational perspective according to which it is neither the elements nor the emergent whole but the relations between the elements (transformations) that become primary through the use of logical procedure. – [Roger Hammond]

John Smith | UK | 1975 | 16mm to digital | 7 min

Des images de magazines et de suppléments couleur accompagnent un texte en voix off tiré de l’ouvrage Word Associations and Linguistic Theory du psycholinguiste américain Herbert H. Clark. Utilisant les ambiguïtés inhérentes à la langue anglaise, Associations retourne le langage contre lui-même. Images et mots œuvrent dans une direction identique/opposée pour détruire/produire le sens. – [John Smith, traduction : film documentaire]

Images from magazines and colour supplements accompany a spoken text taken from Word Associations and Linguistic Theory by the American psycholinguist Herbert H. Clark. By using the ambiguities inherent in the English language, Associations sets language against itself. Image and word work together/against each other to destroy/create meaning. – [John Smith]

Simon Hartog | UK | 1968 | 16mm to digital | 4 min

“Soul in a White Room a été tourné par Simon Hartog aux alentours de l’automne 1968. La musique de la trame sonore est Cousin Jane par Troggs. L’homme est Omar Diop-Blondin, et je ne me souviens plus du nom de la femme. Omar était un étudiant actif en 1968 durant “les événements de mai et de juin” à la Faculté de Nanterre de l’Université de Paris. Au même moment, Godard était à Londres pour tourner Sympathy For The Devil / One Plus One avec les Stones et Omar y était également, apparaissant avec Frankie Y (Frankie Dymon) et d’autres Black Panthers à Londres… Peut-être Michael X aussi. Après son retour au Sénégal, Omar a été emprisonné et tué en détention en 71 ou 72. Je crois que son destin est bien connu des Sénégalais.” – [Jonathan Langran, traduction : SBC Gallery]

“Soul in a White Room was filmed by Simon Hartog around autumn 1968. Music on the soundtrack is Cousin Jane by the Troggs. The man is Omar Diop-Blondin, the woman I don’t recall her name. Omar was a student active in 1968 during ‘les evenement de Mai et de Juin’ at the Faculte de Nanterre, Universite de Paris. Around this time, Godard was in London shooting Sympathy for The Devil / One Plus One with the Stones and Omar was here for that too, appearing with Frankie Y (Frankie Dymon) and the other black panthers in London…. Maybe Michael X too. After returning to Senegal, Omar was imprisoned and killed in custody in ’71 or ’72. I believe his fate is well known to the Senegalese people.”– [Jonathan Langran]

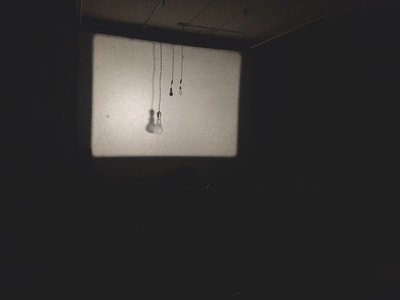

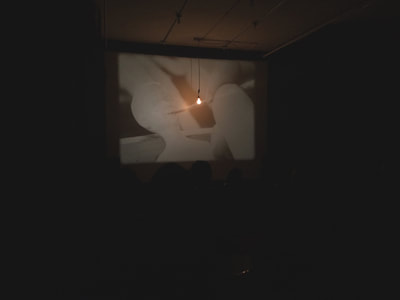

Malcolm Le Grice | UK | 1966 | 16mm & lightbulb | 20 min

Castle 1 est une déconstruction de l’expérience cinématographique où une ampoule électrique pend le long de l’écran, et s’allume ou s’éteint par intermittence au cours de la projection. La majeure partie du film est composée d’images de found footage (utilisation de films trouvés pour en faire un autre) montrant des scènes d’actualité des années 50 et 60. Le son est un ensemble de collages de commentaires, musiques et dialogues assimilés à l’image. – [traduction : espace multimédia et culture numérique gantner]

The light bulb was a Brechtian device to make the spectator aware of himself. I dont like to think of an audience in the mass, but of the individual observer and his behaviour. What he goes through while he watches is what the film is about. Im interested in the way the individual constructs variety from his perceptual intake. – [Malcolm Le Grice, Films and Filming, February 1971]

Translation © Emma Roufs